An analysis of the tricky triangle

I recently had the pleasure of going on a roadtrip to Maine with some of my friends where we did all sorts of awesome things such as go on hikes, grill hot dogs, play board games and visit breweries. On our way there we stopped at a renowned restaurant by the name of Cracker Barrel where I enjoyed a delicious cowboy breakfast that was quite generously portioned. It was here where I discovered what would become my favorite game for many months to come, the tricky triangle (also simply known as “the cracker barrel game”).

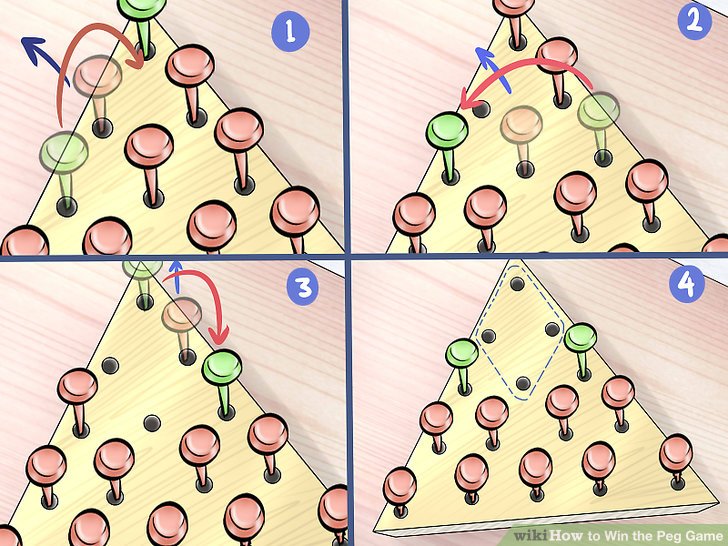

The game

The game is played on a triangular grid with 15 holes and 14 pegs, a peg can “jump” over an adjacent peg for the latter to be removed, with the ultimate goal being to remove all pegs except one.

This proved to be a very difficult task and I didn’t want my cowboy breakfast to get cold so I gave up, never managing to solve it, to the disappointment of my girlfriend, parents and all who are close to me … that is until now!

Solving it with dynamic programming

The problem of removing pegs until one is left can be phrased as a recursive algorithm in the following way: if the board has one peg return the result, otherwise for all pegs that are currently on the board, try to jump them over an adjacent peg to remove it and create a new board, then repeat the algorithm for each of these new configurations.

Importantly, when given a board configuration at a certain step we want to try all different possibilities of legal peg jumps, and see where each of these leads, since there are certain jumps that will lead to configurations that are impossible to solve. This leads to a pretty big number of different subproblems that one has to solve in order to solve the problem up to removing 13 pegs. In fact I estimate that the average number of possible jumps for a given board configuration is around 3. This means that there are $~ 3^{13} = 1.6 \times 10^6$ or around one and a half million paths that one can take.

You may notice however that many of these paths eventually end up at identical board configurations somewhere on the way. For example given 4 pegs and 15 holes there are only ${15 \choose 4} = 1365$ different board configs, and its likely less since due to the rules of the game there are probably some configurations of 4 pegs that are impossible. Thus, if we have already computed the final answer for one configuration, we can simply return that answer. Hence we optimize our algorithm by adding memoization, and make it many times faster.

Results

Well, this blog post would not be complete if I didn’t show one of the solutions that I cheated my way to through the power of my OPTIMIZOOOOR computer code. Here is one possible solution given a starting configuration of empty hole in the middle:

1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1

1 1 0 1 => 0 0 1 1 => 1 0 1 1 => 1 0 1 1

1 1 1 1 1 1 0 1 1 1 0 0

1 1 1 1 0 1 0 1

1 1 1 1

1 1 1 0 1 1 0 0 1 1 1 0 1 0 0 1 0 1 0 0

1 0 0 1 => 1 0 0 1 => 1 0 0 1 => 0 0 0 1

1 1 0 1 1 0 1 1 0 0 1 0

0 1 0 1 0 1 1 1

1 1 1 1

1 0 1 0 0 1 0 1 0 0 1 0 1 0 0 1 0 0 0 0

0 0 0 1 => 0 0 0 0 => 0 1 0 0 => 0 0 0 0

0 1 1 0 1 0 0 0 0 1 0 0

1 0 1 1 1 0 1 0

0 0 0 0

1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

1 0 0 0 => 0 0 0 0

0 0 0 1 0 0

0 0 0 0

0 0

Curiously, it seems that the last peg always ends up in one of the middle holes on the border of the triangle, at least this is the result that my algorithm gives for all (4? because of symmetry?) starting board configurations. Anyway, I hope there is someone out there that found this amusing LOL.

Other interesting results that I had were trying a triangular grid of 10 holes and 9 pegs you can still get a solution and there are 14 unique paths that get you there. Surprisingly there are 1550 ?! unique paths that get you to a solution for the one with 15 holes and 14 pegs. Someone please send this to numberphile or Matt Parker, fank yew.

Finally, this is the algorithm I came up with:

def isValidMove(triangle, p1, p2):

if (p2[0] < 0 or p2[1] < 0) or triangle[p1[0]][p1[1]] != 1:

return False

try:

f = triangle[p2[0]][p2[1]]

if f != 0 or f is None:

return False

except:

return False

# Find whether its a vertical or horizontal

# move

if p1[0] == p2[0]:

# horizontal

btwn = (p1[0], (p1[1] + p2[1]) // 2)

if triangle[btwn[0]][btwn[1]] != 1:

return False

else:

# vertical

btwn = ((p1[0] + p2[0]) // 2, (p1[1] + p2[1]) // 2)

if triangle[btwn[0]][btwn[1]] != 1:

return False

return btwn

memo = {}

def tryOneMove(triangle):

r = ''.join([str(i) for i in chain.from_iterable(triangle)])

if r in memo:

return memo[r]

newTris = []

for i in range(len(triangle)):

for j in range(len(triangle[i])):

p1 = (i, j)

mods = [(-2, -2), (-2, 0), (2, 0), (2, 2), (0, 2), (0, -2)]

for mod in mods:

p2 = (p1[0] + mod[0], p1[1] + mod[1])

btwn = isValidMove(triangle, p1, p2)

if btwn:

nTriangle = copy.deepcopy(triangle)

nTriangle[p1[0]][p1[1]] = 0

nTriangle[btwn[0]][btwn[1]] = 0

nTriangle[p2[0]][p2[1]] = 1

newTris.append(nTriangle)

if not len(newTris):

return [triangle]

memo[r] = min([[tri] + tryOneMove(tri) for tri in newTris], \

key=lambda t: np.nansum(t[-1]))

return memo[r]